Your Lifestyle Has Already Been Designed (The Real Reason For The Forty-Hour Workweek)

Well I’m in the working world again. I’ve found myself a well-paying gig in the engineering industry, and life finally feels like it’s returning to normal after my nine months of traveling.

Because I had been living quite a different lifestyle while I was away, this sudden transition to 9-to-5 existence has exposed something about it that I overlooked before.

Since the moment I was offered the job, I’ve been markedly more careless with my money. Not stupid, just a little quick to pull out my wallet. As a small example, I’m buying expensive coffees again, even though they aren’t nearly as good as New Zealand’s exceptional flat whites, and I don’t get to savor the experience of drinking them on a sunny café patio. When I was away these purchases were less off-handed, and I enjoyed them more.

I’m not talking about big, extravagant purchases. I’m talking about small-scale, casual, promiscuous spending on stuff that doesn’t really add a whole lot to my life. And I won’t actually get paid for another two weeks.

In hindsight I think I’ve always done this when I’ve been well-employed — spending happily during the “flush times.” Having spent nine months living a no-income backpacking lifestyle, I can’t help but be a little more aware of this phenomenon as it happens.

I suppose I do it because I feel I’ve regained a certain stature, now that I am again an amply-paid professional, which seems to entitle me to a certain level of wastefulness. There is a curious feeling of power you get when you drop a couple of twenties without a trace of critical thinking. It feels good to exercise that power of the dollar when you know it will “grow back” pretty quickly anyway.

What I’m doing isn’t unusual at all. Everyone else seems to do this. In fact, I think I’ve only returned to the normal consumer mentality after having spent some time away from it.

I suppose I do it because I feel I’ve regained a certain stature, now that I am again an amply-paid professional, which seems to entitle me to a certain level of wastefulness. There is a curious feeling of power you get when you drop a couple of twenties without a trace of critical thinking. It feels good to exercise that power of the dollar when you know it will “grow back” pretty quickly anyway.

What I’m doing isn’t unusual at all. Everyone else seems to do this. In fact, I think I’ve only returned to the normal consumer mentality after having spent some time away from it.

One of the most surprising discoveries I made during my trip was that I spent much less per month traveling foreign counties (including countries more expensive than Canada) than I did as a regular working joe back home. I had much more free time, I was visiting some of the most beautiful places in the world, I was meeting new people left and right, I was calm and peaceful and otherwise having an unforgettable time, and somehow it cost me much less than my humble 9-5 lifestyle here in one of Canada’s least expensive cities.

It seems I got much more for my dollar when I was traveling. Why?

A Culture of Unnecessaries

Here in the West, a lifestyle of unnecessary spending has been deliberately cultivated and nurtured in the public by big business. Companies in all kinds of industries have a huge stake in the public’s penchant to be careless with their money. They will seek to encourage the public’s habit of casual or non-essential spending whenever they can.

In the documentary The Corporation, a marketing psychologist discussed one of the methods she used to increase sales. Her staff carried out a study on what effect the nagging of children had on their parents’ likelihood of buying a toy for them. They found out that 20% to 40% of the purchases of their toys would not have occurred if the child didn’t nag its parents. One in four visits to theme parks would not have taken place. They used these studies to market their products directly to children, encouraging them to nag their parents to buy.

This marketing campaign alone represents many millions of dollars that were spent because of demand that was completely manufactured.

“You can manipulate consumers into wanting, and therefore buying, your products. It’s a game.” ~ Lucy Hughes, co-creator of “The Nag Factor”

This is only one small example of something that has been going on for a very long time. Big companies didn’t make their millions by earnestly promoting the virtues of their products, they made it by creating a culture of hundreds of millions of people that buy way more than they need and try to chase away dissatisfaction with money.

We buy stuff to cheer ourselves up, to keep up with the Joneses, to fulfill our childhood vision of what our adulthood would be like, to broadcast our status to the world, and for a lot of other psychological reasons that have very little to do with how useful the product really is. How much stuff is in your basement or garage that you haven’t used in the past year?

The real reason for the forty-hour workweek

The ultimate tool for corporations to sustain a culture of this sort is to develop the 40-hour workweek as the normal lifestyle. Under these working conditions people have to build a life in the evenings and on weekends. This arrangement makes us naturally more inclined to spend heavily on entertainment and conveniences because our free time is so scarce.

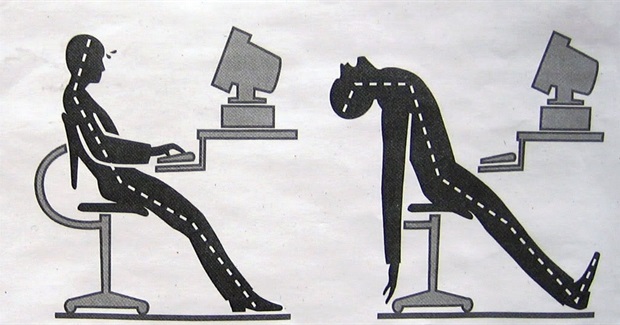

I’ve only been back at work for a few days, but already I’m noticing that the more wholesome activities are quickly dropping out of my life: walking, exercising, reading, meditating, and extra writing.

The one conspicuous similarity between these activities is that they cost little or no money, but they take time.

Suddenly I have a lot more money and a lot less time, which means I have a lot more in common with the typical working North American than I did a few months ago. While I was abroad I wouldn’t have thought twice about spending the day wandering through a national park or reading my book on the beach for a few hours. Now that kind of stuff feels like it’s out of the question. Doing either one would take most of one of my precious weekend days!

The last thing I want to do when I get home from work is exercise. It’s also the last thing I want to do after dinner or before bed or as soon as I wake, and that’s really all the time I have on a weekday.

This seems like a problem with a simple answer: work less so I’d have more free time. I’ve already proven to myself that I can live a fulfilling lifestyle with less than I make right now. Unfortunately, this is close to impossible in my industry, and most others. You work 40-plus hours or you work zero. My clients and contractors are all firmly entrenched in the standard-workday culture, so it isn’t practical to ask them not to ask anything of me after 1pm, even if I could convince my employer not to.

The eight-hour workday developed during the industrial revolution in Britain in the 19th century, as a respite for factory workers who were being exploited with 14- or 16-hour workdays.

As technologies and methods advanced, workers in all industries became able to produce much more value in a shorter amount of time. You’d think this would lead to shorter workdays.

But the 8-hour workday is too profitable for big business, not because of the amount of work people get done in eight hours (the average office worker gets less than three hours of actual work done in 8 hours) but because it makes for such a purchase-happy public. Keeping free time scarce means people pay a lot more for convenience, gratification, and any other relief they can buy. It keeps them watching television, and its commercials. It keeps them unambitious outside of work.

We’ve been led into a culture that has been engineered to leave us tired, hungry for indulgence, willing to pay a lot for convenience and entertainment, and most importantly, vaguely dissatisfied with our lives so that we continue wanting things we don’t have. We buy so much because it always seems like something is still missing.

Western economies, particularly that of the United States, have been built in a very calculated manner on gratification, addiction, and unnecessary spending. We spend to cheer ourselves up, to reward ourselves, to celebrate, to fix problems, to elevate our status, and to alleviate boredom.

Can you imagine what would happen if all of America stopped buying so much unnecessary fluff that doesn’t add a lot of lasting value to our lives?

The economy would collapse and never recover.

Western economies, particularly that of the United States, have been built in a very calculated manner on gratification, addiction, and unnecessary spending. We spend to cheer ourselves up, to reward ourselves, to celebrate, to fix problems, to elevate our status, and to alleviate boredom.

Can you imagine what would happen if all of America stopped buying so much unnecessary fluff that doesn’t add a lot of lasting value to our lives?

The economy would collapse and never recover.

All of America’s well-publicized problems, including obesity, depression, pollution and corruption are what it costs to create and sustain a trillion-dollar economy. For the economy to be “healthy”, America has to remain unhealthy. Healthy, happy people don’t feel like they need much they don’t already have, and that means they don’t buy a lot of junk, don’t need to be entertained as much, and they don’t end up watching a lot of commercials.

The culture of the eight-hour workday is big business’ most powerful tool for keeping people in this same dissatisfied state where the answer to every problem is to buy something.

You may have heard of Parkinson’s Law. It is often used in reference to time usage: the more time you’ve been given to do something, the more time it will take you to do it. It’s amazing how much you can get done in twenty minutes if twenty minutes is all you have. But if you have all afternoon, it would probably take way longer.

Most of us treat our money this way. The more we make, the more we spend. It’s not that we suddenly need to buy more just because we make more, only that we can, so we do. In fact, it’s quite difficult for us to avoid increasing our standard of living (or at least our rate of spending) every time we get a raise.

I don’t think it’s necessary to shun the whole ugly system and go live in the woods, pretending to be a deaf-mute, as Holden Caulfield often fantasized. But we could certainly do well to understand what big commerce really wants us to be. They’ve been working for decades to create millions of ideal consumers, and they have succeeded. Unless you’re a real anomaly, your lifestyle has already been designed.

The perfect customer is dissatisfied but hopeful, uninterested in serious personal development, highly habituated to the television, working full-time, earning a fair amount, indulging during their free time, and somehow just getting by.

Is this you?

Two weeks ago I would have said hell no, that’s not me, but if all my weeks were like this one has been, that might be wishful thinking.

Photo by joelogon